What does Chado; an ancient Japanese tea ceremony, and Capoeira; a Brazilian martial art have in common? They can both increase creativity. Discover how the movements, philosophy and traditions one learns in such practices manifest themselves in creative work.

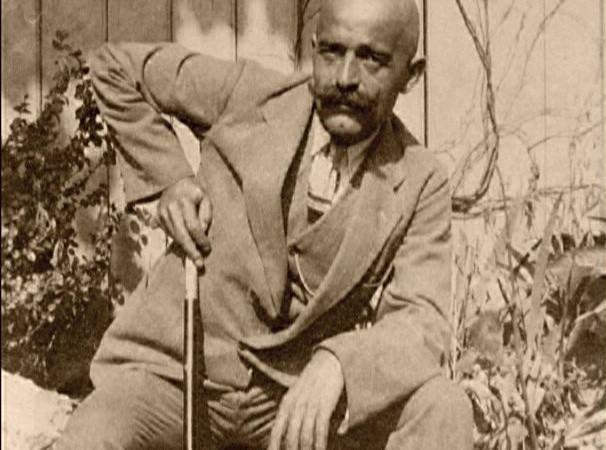

John Middleton Murry on The Price of Leadership

John Middleton Murry, writer of over sixty books, Classics scholar of Oxford, Pacifist, co-operative farming innovator, husband of Katherine Mansfield, best friend of D H Lawrence, and unknown centre of influence for the Bloomsbury Group, was also a devout Christian.

In The Price of Leadership written between the Wars, Middleton Murry laid out his argument for a Christian society. But at the mention of Christianity, don’t roll your eyes and stop reading just yet.

At this point, as an atheist, I normally close the book as perhaps you too are thinking about moving on from this article. Yet, I urge you to continue.

Some of what he wrote may be of interest especially if you feel frustrated and disappointed with your life. And no, this isn’t a preaching of God. Middleton Murry speaks of much more than just turning to the Lord. In fact, he does not talk much about God at all, but argues for the return to a Christian society.

Why?

In short, because it would include a return to self-sustaining communities, where individualism did not exist so much, where there was contentment with simple living, along with an overarching belief beyond nationalism that joined Europe together.

At the time of writing, just before the second War in 1939, many questions about the structure of Government and position of democracy were in debate. Fascism was in the rise in Italy and Germany, communism was well underway in Russia, and the British were figuring out pluralism within Christian education. Capitalism was rearing its ugly head and its antithesis, Marxism, was being touted as the medicine.

What you know, ex post facto, is that the experiment of fascism failed, democracy won and the capitalist path was paved. And here we are now. What Middleton Murry did in The Price of Leadership was to predict the ‘moral chaos’ we find ourselves in.

Moral Chaos

You read, hear and feel moral chaos everywhere, at present. It’s the quarter-life crisis, the disappointment of careers, jobs and life. It’s the failure to understand love, to find ataraxia, to be happy with what you’ve got. To know something just isn’t quite right.

The moral chaos we find ourselves in is silent, as is the mindfulness revolution fighting against it. What Middleton Murry did was to predict it as the end consequence of a second War and the end of a Christian and fundamentally spiritual society:

‘Shakespeare’s King Lear is the truth:

If that the heavens do not their visible spirits

Send quickly down to tame these vile offences

It will come

Humanity must perforce prey on itself

Like monsters of the deep.’

It is the result, he explains, of nationalism and at a singular level, individualism. A return to a smaller, self-sustaining life (in the countryside) with spiritualism as its practical core could be the answer.

Individualism

Individualism, the belief that your needs are more important than those of society, is a relatively modern phenomenon. It grew after the Second World War, yet is not necessarily a negative trait.

Know thyself is the beginning of all philosophical quests and as the spiritual leader George Gurdjieff taught (Middleton Murry’s wife, Katherine Mansfield, would die by Gurdjieff’s side of tuberculosis in 1923), enlightenment is found in creating a ‘permanent, unchanging self’.

Yet, Middleton Murry argued that ‘The function of the Church, as [he saw] it, was to guide and control the growth of individualism.’ It was Christianity’s greatest failure not to do this. He explains how a return to Christian society, properly administered, can help:

‘To get to the root of the matter we have to feel our way back into the past when the village-community was a real commune: when it was cut off from the outer world and was practically self-supporting, when individual possession in the modern sense was very rare. Then, out of the tenth part of the yearly increase, the church and the parson were supported. And as the church was much more than a place of worship- a storehouse, a place of safe-keeping, and a meeting-house: so was the parson much more than a hierophant of the mystery of God.’

The responsibility one has to such a community inherently means the destruction of individualism.

The feeling of disappointment found in cities

Speaking of those in London and feeling depressed,

‘…they have been intolerably let down; and somewhere within themselves, vaguely but incontrovertibly, they know it. But what it is that has let them down, that they do not know. And who can tell them?’

Middleton Murry is speaking of the wider powers and influences that be: of class, capitalism and more:

‘…By the end of the War, life in a great city had become utterly intolerable to me… though the desire to escape the city was mainly unreasoned and instinctive. To me, the city and the War were unanalysably one single thing. The great city remained the symbol of that mass-hysteria and mass-degradation of which it had been the forcing-house – the hysteria and degradation which had horrified me in modern war, and which had thrust me into a condition of isolation, at once intolerable and unescapable.

‘Very gradually, in the country a sense of community returned to me. I now had real neighbours. And slowly, my religious faith, which had been real, but private and ecstatic, passed out of my consciousness into my being. At the same time my work and my living became continuous: the impatience of the intellectual dissolved away. There ceased to be any essential difference between my work at the desk, at or between my work and my wife’s, my maidservant’s or my man’s. I underwent, quiet and unobtrusive way, what I suppose is meant by the return to Nature.’

Take-away points

John Middleton Murry’s argument is that individualism coupled with capitalism, and without spiritual restraint (leadership), ends in the moral chaos we now find ourselves in.

A return to smaller village-like communes such as that found in medieval Christian society offers a solution (one that he’d later prove by setting up a co-operative farm in East Anglia).

‘What other end can life have but the simple living? To live to an end beyond living seems to me now an insanity.’

And I’m inclined to agree with him. While I do not think it is as straightforward as shifting everyone back into agriculture, one cannot deny the beating heart of capitalism, the city, is relentless as it is frustrating, and that we find ourselves in constant self-turmoil. Liquid life, as sociologist Zygmunt Bauman puts it.

That we seek to escape it in retirement, holidays and life-crises can only be further proof that is it far from the natural setting we feel happy in. Therefore, perhaps there is something in the idea of moving to or developing a self-sustaining community, and engaging more in a non-religious spiritual path.

What practical steps can we take right now from it?

Probably, just to take a holiday and have a think about everything. And with that, I’m packing my bags to go to Brazil.

Previous Post: In Search of the Miraculous by P. D. Ouspensky

Liked what you posed about Ouspensky/Gurdjieff. Where are you these days, havn’t seen a recent post. That being said, I noticed there are no dates on your posts which would be useful for context