John Middleton Murry was a prolific writer and intellectual. So why did he call for a return to early 19th Century Christian society?

Assumptions: How to test and destroy them

“Homo Sapiens are arrogant,” said Dr Clarke, “We think we know more than we do.”

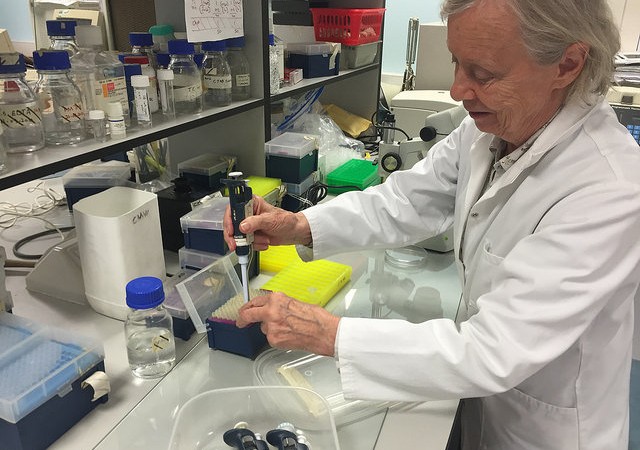

Dr Ann Clarke is a scientist and co-founder of The Frozen Ark, a global conservation project to collect and freeze the genetic material of over 15,000 endangered species.

We were discussing the topic of curiosity: How it was a unique interest in snails that led her husband, Professor Bryan Clarke, to create the Frozen Ark.

This article is a write up of that conversation. About how assumptions are dangerous and how they stop you from being curious. I also share how you can create a system to test your assumptions with real examples.

Assumptions kill curiosity

I explained my theory to Dr Clarke that an assumption of knowledge kills curiosity.

“There’s an assumption,” I said, “that we know everything. When I walk through a forest I don’t know what the trees are, I don’t know what they’re called. But I think, I could just take a photo and go on Wikipedia to find out – if I wanted to.

“Or imagine if I find an interesting insect I hadn’t seen before. I assume that someone somewhere already knows about it. And so I move on and continue with my day.”

Dr Clarke explained that the assumption of knowledge was wrong. We should never assume something is already known and we should always seek to discover the answer for ourselves.

She gave an example from Biology:

75% of invertebrates are yet to be named. That means if you find an insect (probably in a lesser-known area such as the Brazilian rainforest), there’s a three-in-four chance that it’s unknown.

Go to the rainforest, put a sheet under a tree, shake it, and you will discover new species. Our knowledge is not absolute.

This seems obvious. Of course our knowledge is not absolute for if I knew everything I wouldn’t need to work.

Yet, turn this question on its head: What knowledge do you think you have, that you don’t? OR, what knowledge do you think we have, that we don’t?

Charles Darwin said,

A man who dares to waste one hour of time has not discovered the value of life.

If you’ve ever read his lesser known The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, you’ll discover more so than through On the Origin of Species that he was curious to a degree of infatuation.

Is there knowledge that you presume people to know, that’s already out there, that’s stopping you from being curious? Stopping you from discovering it for yourself?

When you walk through a park, can you name all the trees? If not, do you presume someone else can? Yes. And here lies my point.

An assumption of knowledge kills curiosity, kills the drive to discover, kills the oomph to try.

- You assume someone knows the answer

- You assume it’s already been done

- You assume they know about it

Daniel Kahneman, Nobel Prize winner and bestselling author of Thinking, Fast and Slow (a book you should immediately order), proved that we jump to conclusions a thousand times a day; our brains are wired for lazy, quick thinking. We’re easily swayed by tiny influences. For example, in America you are more likely to be set free if your Parole Officers have just eaten lunch.

Our most basic assumptions are often wrong and you must test them, rigorously and methodically to see if they are holding you back.

- You assume he/she doesn’t like you

- You assume you’re not good enough for the job

- You assume you won’t be good at it

- You assume it’ll be difficult

- You assume it’ll take loads of time

Create a system to test your assumptions

What is your assumption and how can you test it?

I assumed top-level people would not have the time to speak to me.

So I created a system to test my assumption. For one hour a week (I do it on a Friday afternoon), I research five A-players: world class professionals / experts in their field, and I send them a message asking for a coffee.

People I am genuinely interested in, those I have followed for years and am a little bit star struck by.

Dr Clarke was such a person. I had an assumption that she would be out of reach, too busy and uninterested to speak to me. Yet, all it took was an email. She invited me to Nottingham University to visit her lab, we did a podcast interview for an hour and ten minutes, drank tea, ate cake and spoke of how J. R. R. Tolkein (author of Lord of the Rings) read her stories as a child. If you listen to the podcast (launching Spring 2016) you’ll hear how she even suggests I would make a good Director of her charity.

Since then my assumption has consistently been proven wrong.

Set time in your week and create a rule to test your assumption. Don’t think he / she likes you? Don’t think, test it: Ask them out for a drink.

It’s important to test your assumption more than once

Some people I got in touch with did not say yes. In fact, the first three people I contacted said no or did not respond. Since then however, more people have said yes than no. I simply had a ‘bad run’ right at the beginning.

This is why it’s important to have a methodological system and not rely on the results of just one test.

Sleeping longer will make you less tired, right? Wrong. Read this article I wrote on how to wake up not feeling tired and test it a few nights for yourself. You may find that sleeping less can help you feel more awake. Test your assumptions.

Similarly, I experimented with lucid dreaming. I followed the methodology of Stephen LaBerge and Howard Rheingold set out in Exploring the World of Lucid Dreaming and tried to wake up 3 – 6 times per night midway through my deep sleep cycle (REM) to record my dreams. I failed to note anything coherent or even eligible for the first three weeks. I assumed it wouldn’t happen. Then that night, I had a lucid dream.

Create a system and test it:

- What is your assumption?

- How can you test it?

- How many times and how frequently are you able to test it?

Do not let the assumption of knowledge kill your curiosity. If you do not know it, do not assume someone else does. Discover the knowledge. If it’s not there, continue with your examination and find it for yourself. Be an explorer in life and in everything you do. Like a picture with more pixels, or sides to a story, curiosity adds depth to your world.

Image: Dr Ann Clarke of The Frozen Ark. I took this photograph at Nottingham University when she kindly invited me to take a look at the lab.