When is it good, from a moral standpoint, to buy something?

In Search of the Miraculous by P. D. Ouspensky

There are some books where half of it is gobbledegook, and the other half is pure genius. In Search of the Miraculous by P. D. Ouspensky is such a book.

If you were a hippy in the 1960s, this was compulsory reading. Albeit even then, you were 50 years late.

P. D. Ouspensky was a student of George Gurdjieff, a spiritual leader who developed The Fourth Way, a practical course of spirituality created after traveling the world investigating ancient schools of thought and religion. Ouspensky was an intellectual who learnt about Gurdjieff by chance, and wrote about his discoveries, In Search of the Miraculous.

There is so much incredible content in this book I have struggled to decide what to share and in what order. You simply must read it yourself, ignoring the half including dodgy science. I won’t lament on that now, for there is much more insight to gain in the good stuff.

I discovered Gurdjieff when learning Katherine Mansfield, the New Zealand writer and wife to my great grand-father John Middleton Murry, died by his side.

First and foremost, Gurdjieff’s teachings are about waking up. He explains that you are asleep. That you are not conscious of yourself, that you are not being.

Now, upon first reading this I thought here we go. But following Ryan Holiday’s advice (author of The Obstacle is The Way) I read the first 100 pages before giving up, and reached a chapter on self-remembering. Gurdjieff is quoted,

‘To awaken means to realise one’s nothingness, that is to realise one’s complete and absolute mechanicalness and one’s complete and absolute helplessness.’

It’s a statement that you will have contemplated before. All science, philosophy and religion leads to that fact. Amor fati, as Nietzsche would say.

Yet, what Gurdjieff did that I had not encountered before, was to teach a practical method of exercising this: of awakening.

Self-observation

Remember yourself, Gurdjieff explains. Right now, ask, ‘Am I here?’ Feel that you are looking at yourself. Your thoughts, your actions, your posture, your situation, your facial expressions, every muscle tensed, breath exhaled, sound heard, sight seen.

‘If a man… tries to remember himself, every impression he receives while remembering himself will, so to speak, be doubled. In an ordinary psychic state I simply look at a street. But if I remember myself, I do not simply look at the street; I feel that I am looking, as though saying to myself: ‘I am looking.’ Instead of one impression of the street there are two impressions, one of the street and another of myself looking at it.’

And it is an odd experience to ‘remember yourself’. I first tried this on an escalator at Oxford Circus tube station. ‘Am I here?’ I asked. Then, I experienced the moment in its entirety.

What it made me realise, as I believe it will for you too, is how much we miss. For example, through daydreaming, our imagination and thoughts. The commute has to be the greatest example – years of traveling from home to work, work to home, and yet not a single clear memory.

It is through self-observation that you can learn to awaken:

‘Self-observation brings man to the realisation of the necessity for self-change. And in observing himself a man notices that self-observation itself brings about certain changes in his inner processes. He begins to understand that self-observation is an instrument of self-change, a means of awakening. By observing himself he throws, as it were, a ray of light onto his inner processes which have hitherto worked in complete darkness. And under the influence of this light the processes themselves begin to change. There are a great many chemical processes that can take place only in the absence of light.’

Knowledge and Understanding

The principle demand of Gurdjieff’s fourth way is understanding.

‘Knowledge is one thing, understanding is another.’

It is usually the case that when you truly understand something, you find beauty in it. It is also the case that it affects your being. For example, in Capoeira, the Brazilian martial art I practice, Mestres don’t fight, they play (or as some say, they play chess with their bodies). In the same way, linguists don’t just know words, they enjoy the natural intonation and rhythm of speech. Composers hear written sheet music. Mathematicians see shapes.

‘…The thinking apparatus may know something. But understanding appears only when a man feels and senses what is connected with it.’

Thus one must understand what it means to be awake. And you can achieve this through practice of self-observation. Ask yourself, am I here?

Developing a permanent self

What you inevitably discover through self-observation (as any experienced Anthropologist can attest), is that ‘a man is never the same for long. He is continually changing. He seldom remains the same even for half an hour.’

Who you are to your boss is not the same as who you are to your best friend. And who you are to your best friend is not the same as who you are to your spouse, parents or siblings. Equally, who you are to yourself is also ever-changing. One moment you are working studiously, then next, daydreaming.

‘Man has no permanent and unchangeable I. Every thought, every mood, every desire, every sensation, says ‘I.’ And in each case it seems to be taken for granted that this I belongs to the Whole, to the whole man, and that a thought, a desire, or an aversion is expressed by this Whole. In actual fact there is no foundation whatever for this assumption… Man has no individual I. But there are, instead, hundreds and thousands of separate small I’s, very often entirely unknown to one another, never coming into contact, or, on the contrary, hostile to each other.’

Gurdjieff’s fourth way is about understanding this through self-observation, and with practice developing an awakened permanent self. Conscious, honest and aware.

In Search of the Miraculous has much more insight, but this is the practical gist of it. Gurdjieff allows you to come to terms with that nothing matters and everything happens. If you want to do something about it, it is necessary to be. And first, it is necessary to understand what to be means.

I recommend reading it for as long as you ignore the bizarre theories of creation, hydrogen and various other chemistry disillusionments. Compliment your reading with John Middleton Murry’s The Price of Leadership which calls for a return to 19th Century Christian society and see whether you can find nuggets of gold there too.

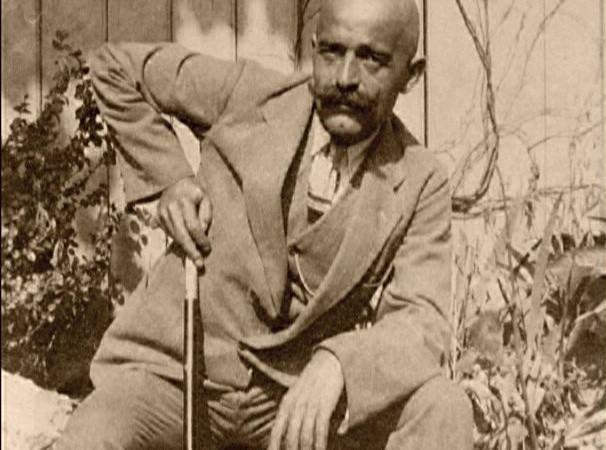

Picture: George Gurdjieff

Thanks Tom. Curious that I actually didn’t find the other half to be gobbledygook. But enjoyed your review nonetheless.

Thanks for the overview of this book. Read and enjoyed it quite a bit!